PAOC Spotlights

This is What a Scientist Looks Like

Researchers from MIT EAPS celebrate women in science at MIT Museum’s Girls Day.

“Close your eyes and think about a scientist that is building a time machine,” said Kristin Bergmann. “What does your scientist look like? What does the time machine look like? Now open your eyes and I will show you my time machine.” Bergmann reveals a pair of hiking boots and a picture of her standing on a cliff face looking at ancient rocks deposited there by an ocean to an audience at MIT Museum’s Girls Day. “With these boots, I travel back in time. Raise your hand if I am the scientist you were imagining and this is the time machine that I was building.”

Bergmann, the Victor P. Starr Career Development assistant professor in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS), was one of many environmental scientists from the department and MIT, in addition to other groups from Harvard, Northeastern and BU participating in the MIT Museum’s Girls Day earlier this month, encouraging girls and women to become scientists.

Now in its sixth year, the bi-annual event held in March and November celebrates women in the science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields and demonstrates diversity in science among the people involved and their career choices. It also helps to combat the US gender gap in science by inspiring girls to pursue STEM professions. The Girls Day theme changes each time, and this month, 823 guests came out to explore environmental science: listening to talks from EAPS women scientists and a freelance science writer, as well as participating in eighteen hands-on activities. Members from EAPS including the Program in Atmospheres, Oceans and Climate (PAOC) joined the MIT Women in Course XII, MIT Undergraduate Association of Sustainability, MIT Museum Teen Programming Council, MIT Biological Engineering, MIT Women’s Graduate Association of Aeronautics and Astronautics and the MIT Society of Women Engineers to investigate topics including geology, paleoclimatology, gemstone identification and topological maps; ocean physics, ecosystems and pollution; and atmospheric dynamics and viewing the Earth from space.

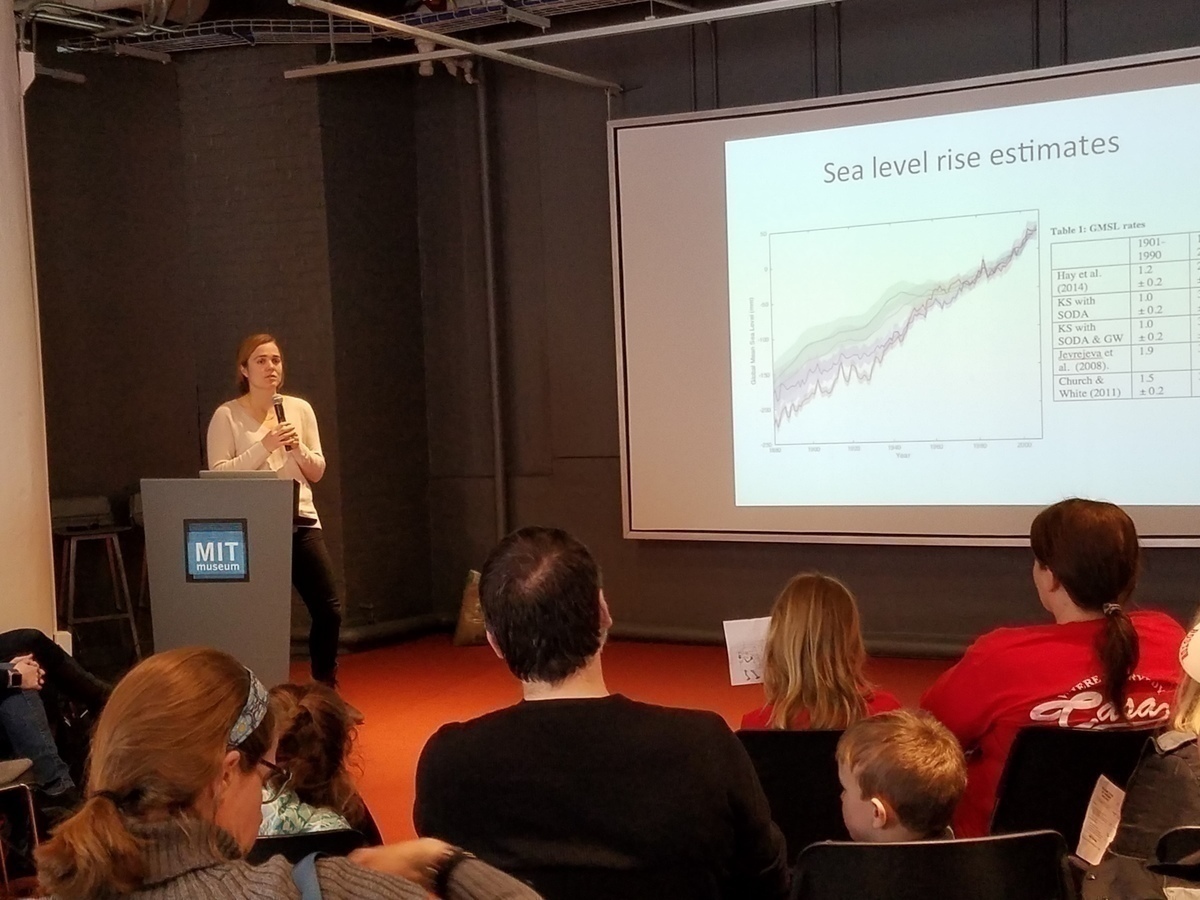

Enthusiastic talks from MIT women in science set the tone for the day. After Greta Friar, a graduate of the MIT science writing program and a freelancer, kicked off the morning session, Megan Lickley, was next to speak. As a third year graduate student in EAPS PAOC and an occasional participant in Joint Program in the Science and Policy of Global Change work, Lickley spends her time modeling climate change-related sea level rise, how it’s measured and its costs. During her talk, Lickley explored causes for this rise particularly in Boston, where these young girls and women call home. She looked at ice melt, thermal expansion, sinking lands, ice sheet fingerprints and ocean dynamics in around the world and asked the audience to hypothesize why Boston might be experiencing sea level rise more than other locations.

While Lickley’s path into the study of sea level rise took a meandering route, she’s glad that she’s found it and can share her passion with others. “It took me a several years to figure out how I wanted to work on the climate change problem. I tried various other things and I hoped to convey [at Girls Day] that there is value to exploring before deciding on a career. I love my work,” and, “I think it’s important for girls to see women who love their jobs.”

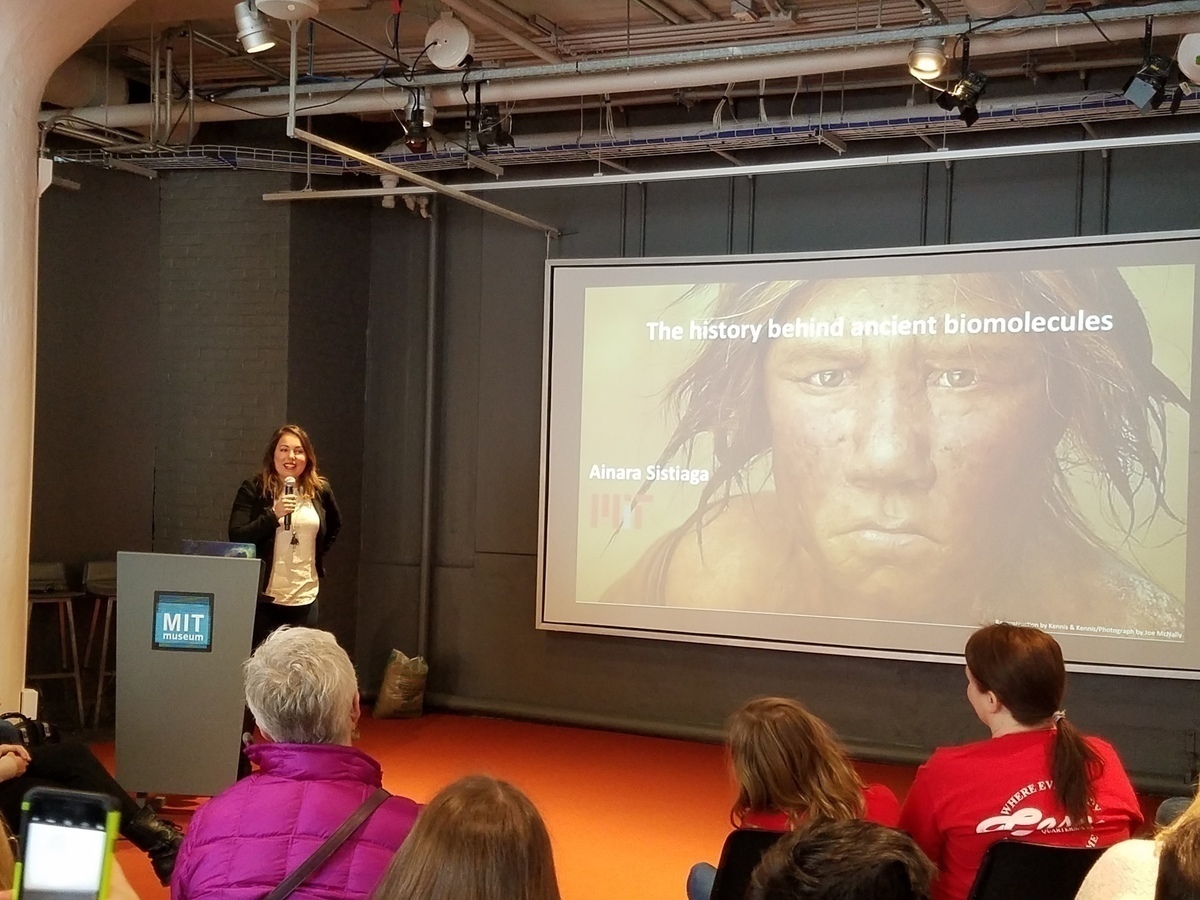

Unlike Lickley, Ainara Sistiaga knew from a young age that she wanted to study archaeology, inspired by a history book given to her by her mother exploring how people in Egypt lived in the past. Now, Sistiaga, the Marie Curie postdoctoral fellow at MIT and the University of Copenhagen working in the Summons Lab, investigates human evolution through paleolithic archaeology and organic chemistry. Growing up, movies often depicted archaeology as a dangerous field suited for strong men like Indiana Jones, but then Sistiaga learned of Mary Leakey’s research, tracing the origins of Homo sapiens back to the great apes. If Leakey could do it, why couldn’t she? Sistiaga travels the globe collecting and analyzing fecal samples from Neanderthals, mummies and modern populations to investigate the role of diet and the gut microbiome in human evolution. She hopes to learn more about environmental pressures our ancestors faced and why the Neanderthals died out.

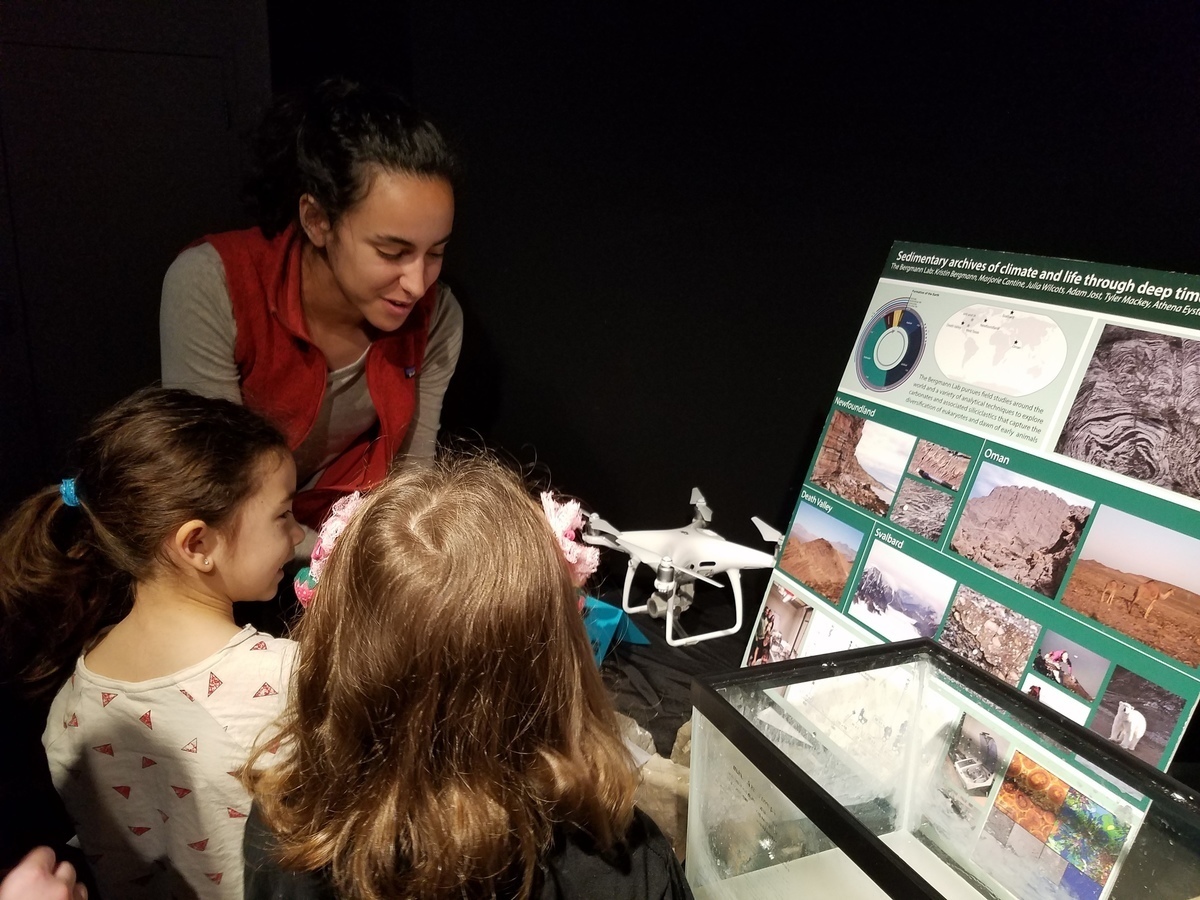

Kristin Bergmann’s hiking boots “time machine” take her to far reaches of the globe, back to an age long before Neanderthals. As a geobiologist, she’s trying to figure out why the Earth is special: Why did it take about 3 billion years for life to transition from small, simple microbes to large complex animals? For this, she turns to rocks. “Rocks capture secrets about the history of our planet and the life that has lived on it,” Bergmann told an attentive audience. Her work has focused on marine carbonate sedimentary rocks and fossils, analyzing them in the field and the lab in order to better understand how the chemistry and climate of the oceans and atmosphere affected the evolution of complex life.

In her talk, Bergmann pushed the young girls and their families to reevaluate what they think a scientist is and how you become one. She produced one of her elementary school report cards, which showed some Bs and even Cs. “I don’t want you to be discouraged if you get a B or C in school. I was not discouraged. None of this report card, to me, is a sign of failure. It was a sign that I was learning hard things.” As a former middle school Earth and life science teacher and now EAPS professor, Bergmann understands what it’s like to be an educator and a lifelong investigator. Her teaching style, subject matter and media foster curiosity within all types of learners: visual, auditory, kinesthetic, etc. Different scientists have different skills and take distinctive career paths. “Three things I want you to remember,” Bergmann said on Girls Day. “First, scientists can be explorers; they don’t always work in a lab. I’m probably not the scientist you were picturing building the time machine. Second, be creative and be curious, even if it means getting some Bs or Cs along the way. Learn from them. And third, I didn’t know that I would be a geologist when I was your age, but when I found geology, I loved it. I kept doing it, and I kept taking risks along the way.”

When asked by a young girl if it’s hard to be scientist, Bergmann replied, “I love what I do…and I work with great people. We’re all excited to tackle these big questions. So I don’t think it’s difficult to be a scientist.”

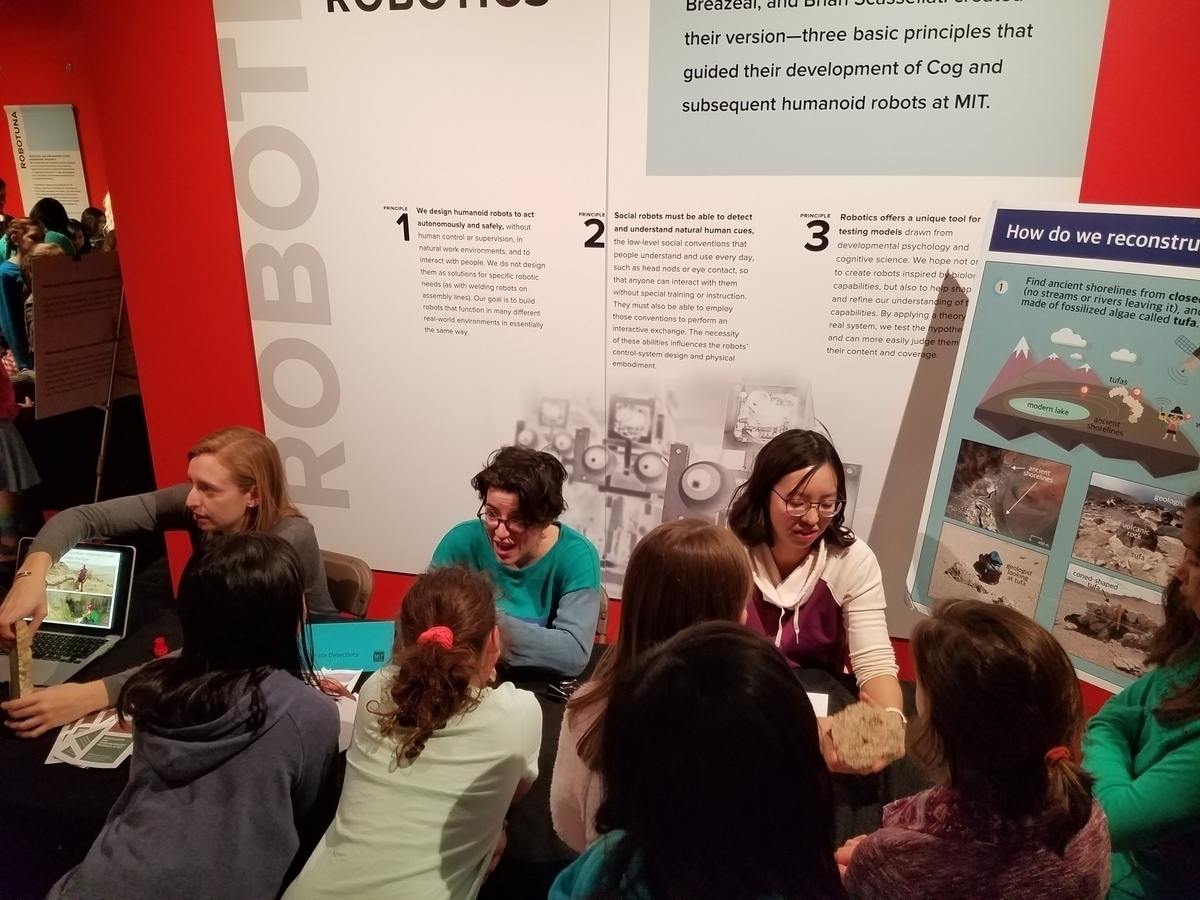

Afterward, guests were encouraged to go on a scientific scavenger hunt: visiting all of the exhibit stations and collecting a stamp after completing the activity. EAPS faculty, students, and volunteers were out in full force, sharing the latest in oceanographic, meteorological and paleoclimatological research, data collection and explorations.

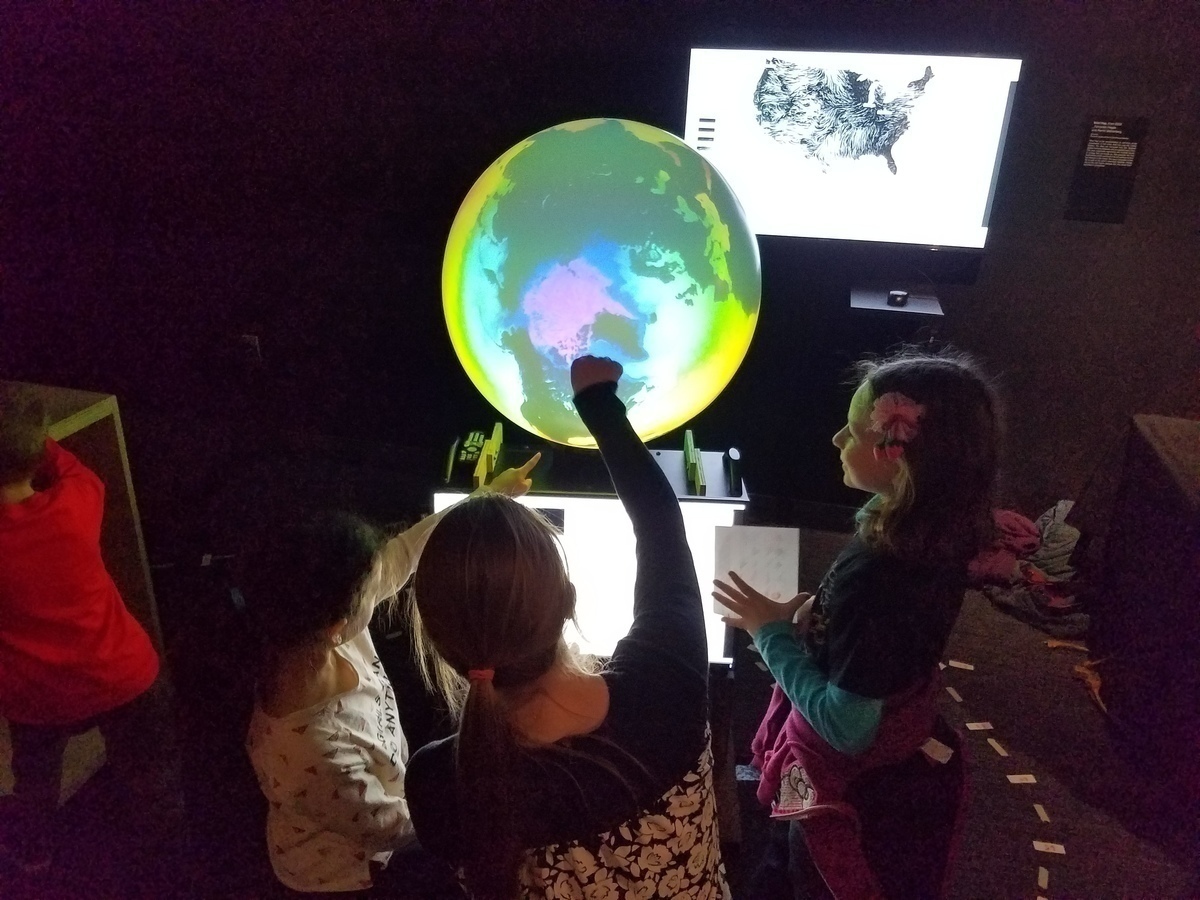

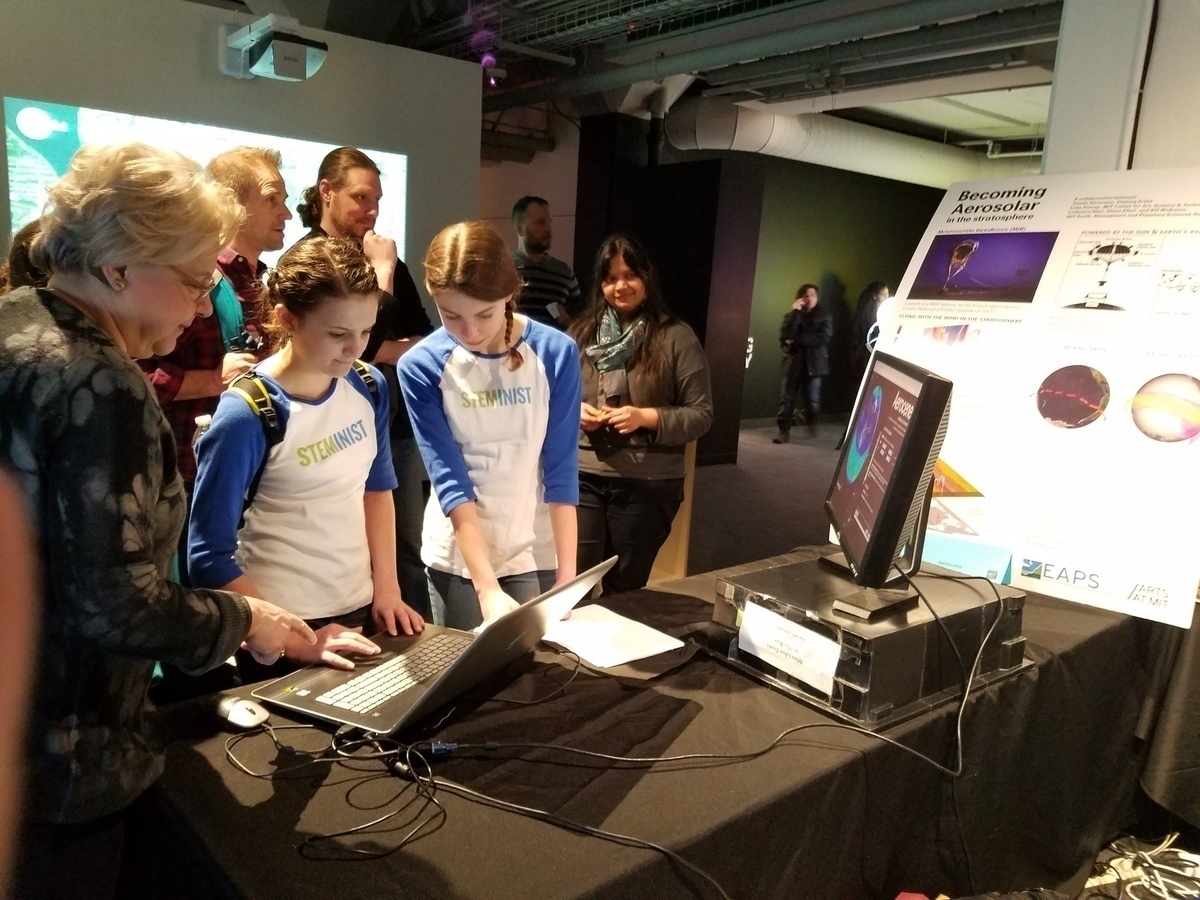

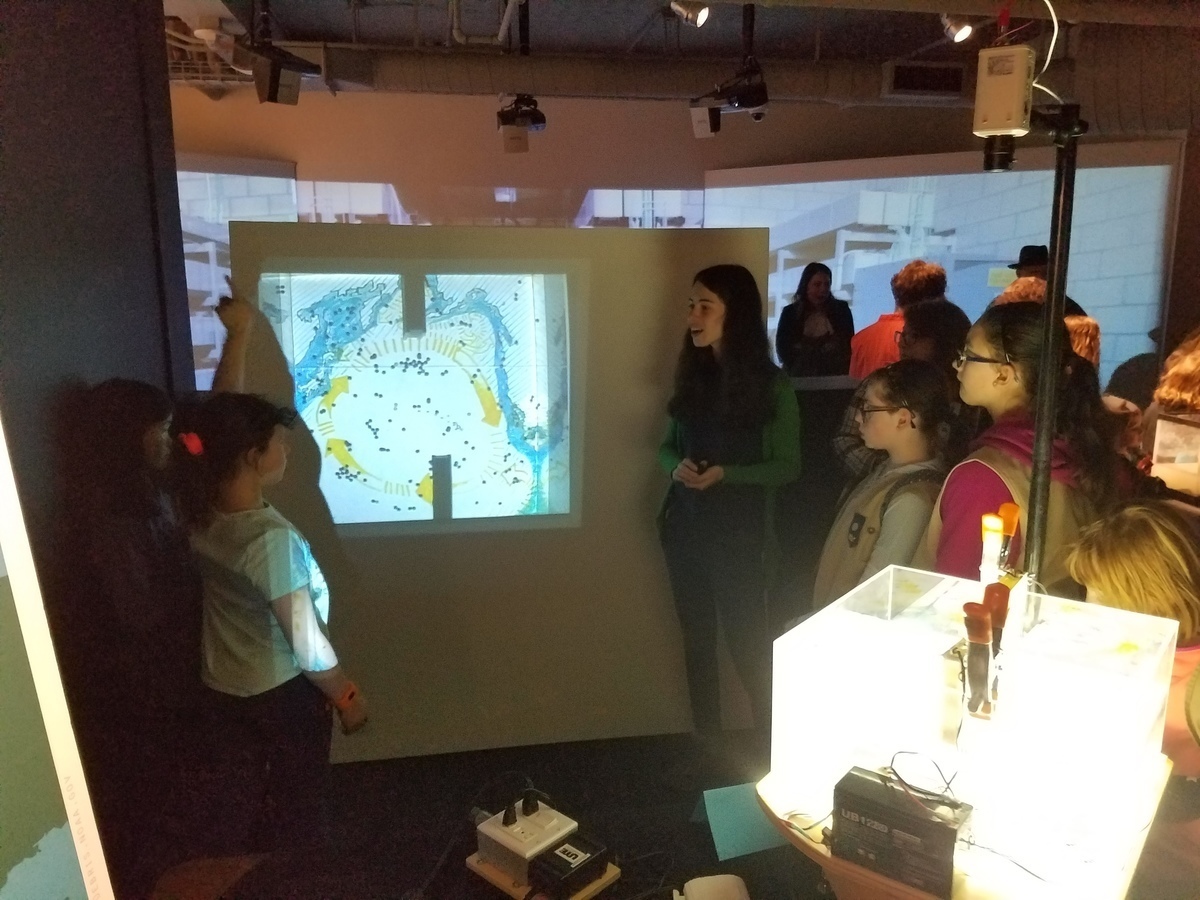

Several EAPS groups came out to support the event. Professor Kristin Bergmann along with graduate students Julia Wilcots and Maya Stokes had a ripple tank and an impressive rock display: some with ripple patterns, one with beautiful shells that was once deposited in Ohio in an ocean and another that was about a billion years old. Seeing these rocks challenged audiences to think about ancient landscapes and what environmental pressures might have kept life small. The McGee Lab’s Gabi Serrato Marks, Michaela Fendrock, Christine Chen showed guests how they use information from stalagmites, lake deposits and other marine sediments to reconstruct ancient precipitation and wind patterns. They use this to see how these patterns responded to past climate changes in order to understand how rainfall might change in the future. Graduate students Astrid Pacini, Madeleine Youngs and professor Glenn Flierl helped guests shift their frame to view to global dynamics of ocean and atmospheric currents, weather patterns, climate proxies and more on the iGlobe, a large computerized spherical display. On a path laid out around the iGlobe, guests could “walk the Gulf Stream,” experiencing how fast the water moves north and then slows and meanders back south. MIT’s “Aerocene” display — a project developed by MIT CAST visiting artist Tomás Saraceno in collaboration with EAPS scientists Lodovica Illari, Glenn Flierl, Bill McKenna—to calculate the trajectories of a balloon-like structure around the globe.

The hypothetical flight paths take into account atmospheric data and physics, and depend on when and where (in the world and atmosphere) the structures are launched. Using the interface, Illari along with graduate students Catherine Wilka and Rohini Shivamoggi invited guests to “launch” virtual balloons, challenging them to land in a location of their choosing.

Postdoc Jonathan Lauderdale from the Darwin group showed guests how ocean modelers turn marine ecological phenomena into mathematical relationships, in a popular “bugs to bytes” game. By “hunting” for Swedish Fish while blindfolded, Girls Day attendees could experience how food consumption by predators scales with food abundance to a point, after which there is an abundance of available prey, supporting a premise put forth by ecologist Crawford Stanley (Buzz) Holling. Meanwhile, graduate students Mara Freilich, Tristan Abbott and Henri Drake along with lab assistant Bill McKenna and professor John Marshall illustrated the physics around ocean gyre circulation, specifically the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” with a Weather in a Tank demonstration. Using a rotating tank of water with fans blowing on it to simulate the atmosphere and ocean currents that drive the Pacific Ocean gyre, audiences dropped paper bits into the swirling water; these pieces eventually found their way into the middle of the tank. An overhead camera locked to the turntable and projector allowed audiences to see the effect within the spinning framework.

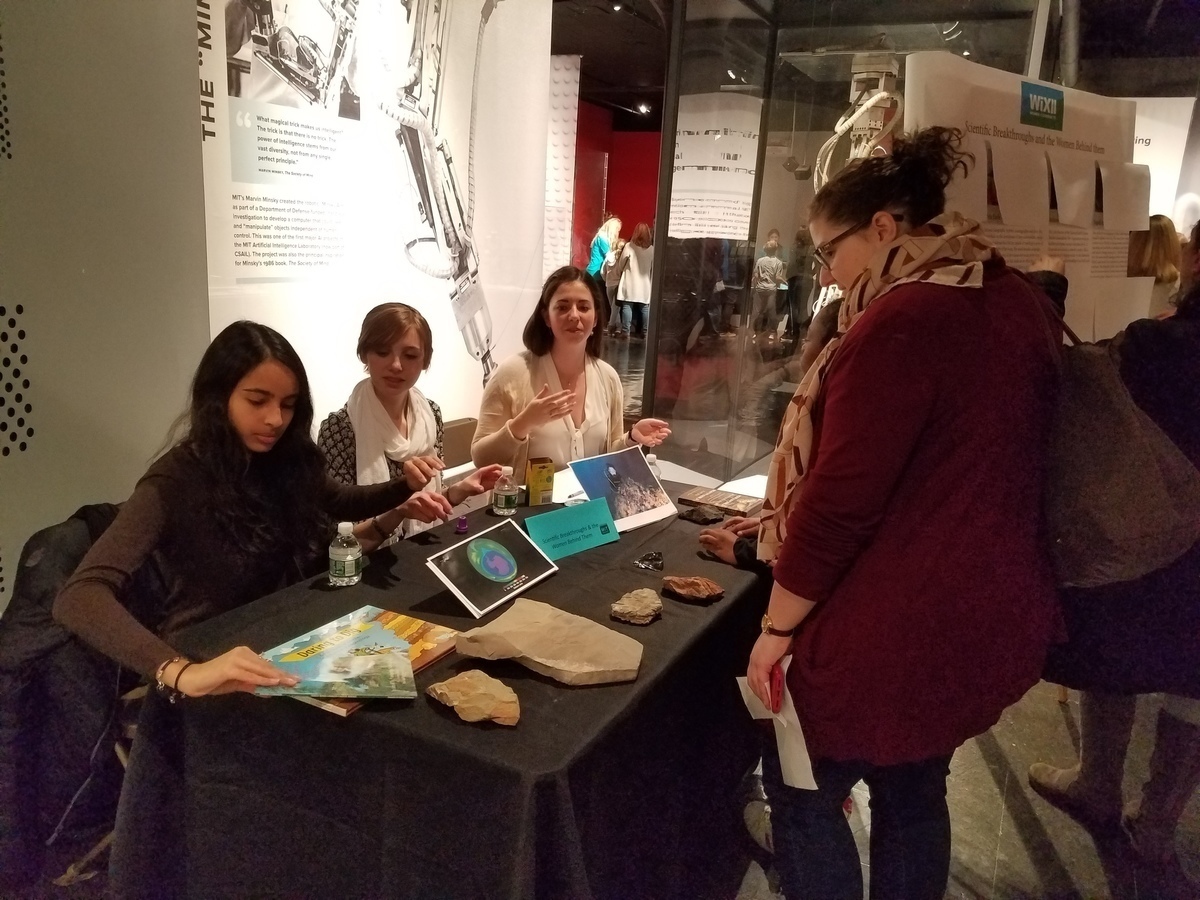

Graduate students and WiXII (Women in Course 12, which is EAPS) members Kelsey Moore, Ellen Lalk, Meghana Ranganathan, Jeemin Rhim, Clara Sousa-Silva, Suzi Clark presented “The Women Behind Scientific Breakthroughs.” Here, attendees learned about pioneering women scientists and their research, one of which was EAPS own Susan Solomon. They then matched the story of the researcher’s work to one on a poster board and revealed her picture.

A recent study showed that outreach efforts by female scientists—like EAPS participation at the MIT Museum’s Girls Day, encouraging young women to pursue science careers—might be paying off. When asked to draw a scientist, US kids aged 5 to 18 are increasingly depicting women, jumping from less than 1% to about 34% over 5 decades, and those sketched by girls was over 50%. This trend follows an uptick in the number of women in science professions. While there are likely many reasons for this, one is certainly mentorship and interaction with women in scientific fields, which EAPS proudly supports.

Participation was supported by a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant from Frontiers in Earth System Dynamics (FESD).