PAOC Spotlights

Study: Ocean Currents Change with Seasons

The strength of ocean currents change with the seasons, which have implications for both ocean life and climate according to a new MIT study.

***

As the seasons change, so too does the strength of ocean currents. A new study from MIT researchers published last month in Nature Communications provides evidence that not only do certain currents become stronger in certain seasons, but also that this seasonality affects both marine life and climate.

The ocean and atmosphere are inextricably linked, and work together to move water and energy across the globe. It’s not surprising then that they have similar physical attributes. MIT Oceanographer Raffaele Ferrari and Jörn Callies, a graduate student in the MIT-WHOI Joint Program in Physical Oceanography, are interested in submesoscale currents—“the ocean equivalent of the atmospheric fronts we experience as weather,” said Ferrari. Elucidating the dynamics of these currents could help us better understand the exchange of properties in the ocean, as well as climate.

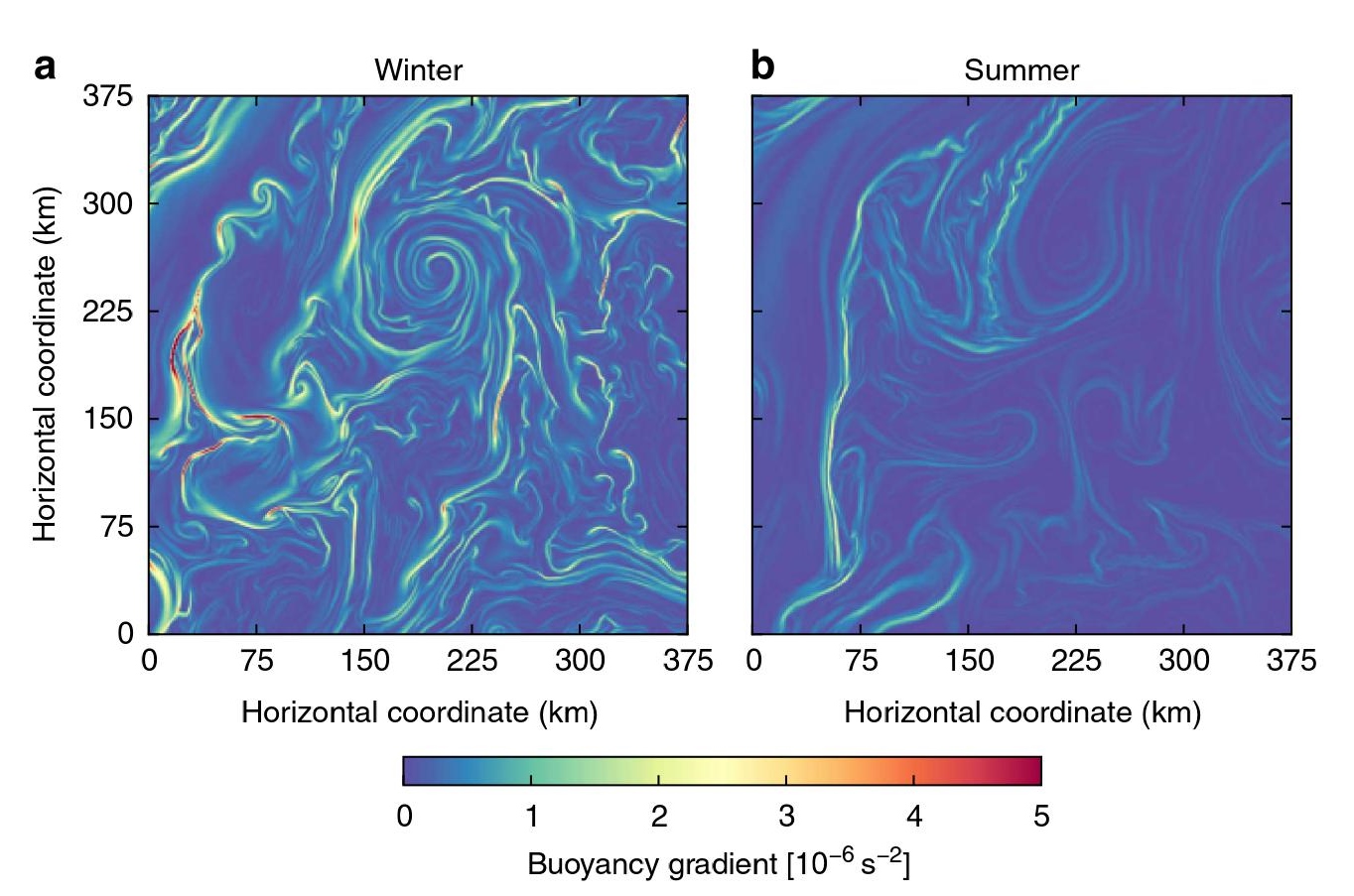

Ferrari, Callies, and colleagues analyzed data collected by the Oleander project and the Lateral Mixing Experiment and found these currents are much stronger in winter than summer. In winter, strong winds and sea surface cooling mix the upper ocean creating deep mixed layers that are prone to instabilities. It is these instabilities that generate stronger currents, according to the study.

Submesoscale currents are important because they create a corridor between ocean layers, allowing the upper ocean to exchange heat and carbon with the deep ocean in return for nutrients. “Marine life respond to these currents just as we respond to weather patterns that affect our lives,” said Ferrari. Where we depend on rainclouds to water our crops, phytoplankton and other marine organisms depend on these currents for their daily dose of nutrients.

However, just as some seasons on land experience more rain than others, in the ocean, the currents in some seasons provide more nutrients than in others. This is especially true in winter when the ocean’s mixed layer deepens, resulting in stronger currents that bring more nutrients to the surface for phytoplankton to feast on come springtime.

While the upper ocean receives an influx of nutrients, submesoscale currents inject heat and carbon into the deep ocean where they are stored for an extended period of time. Changes in current strength and formation could therefore affect Earth’s climate. Future research will investigate the effects of this current seasonality on the general circulation of the ocean and take a closer look at potential climate implications.