PAOC Spotlights

Nautical Day at the MIT Museum

"Can we eat them?"

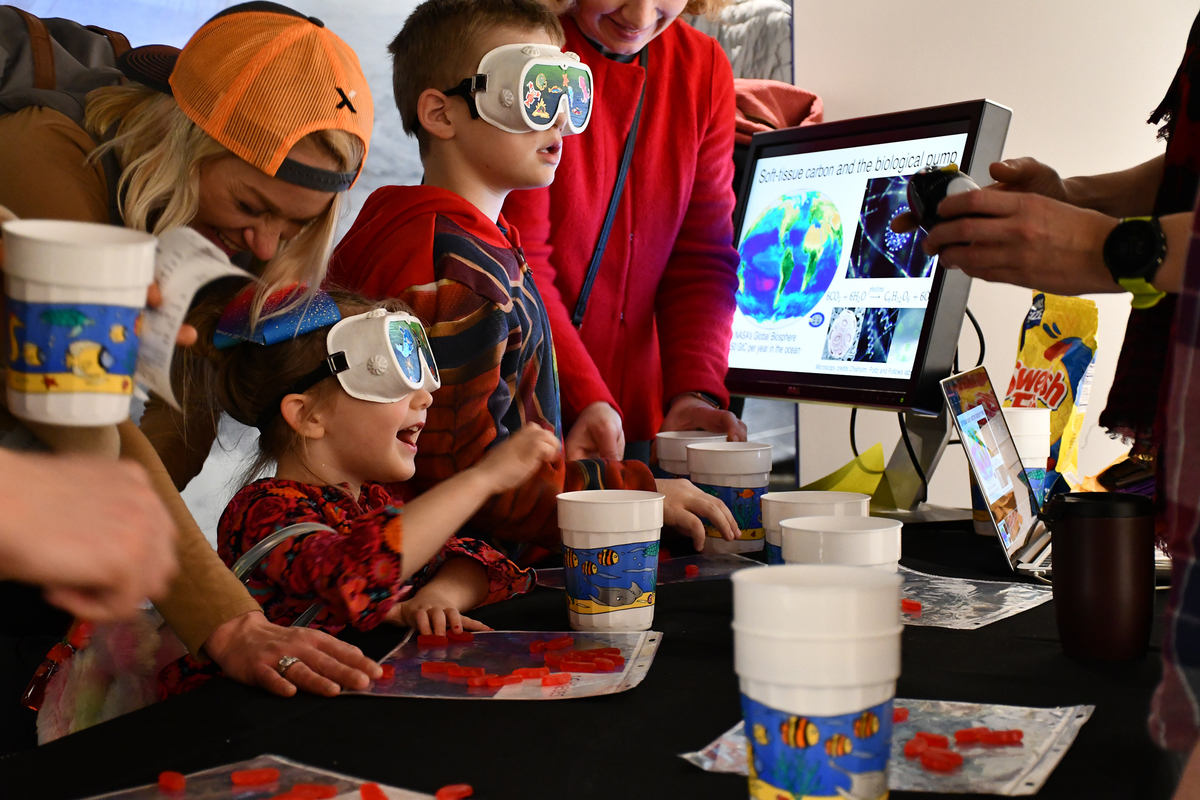

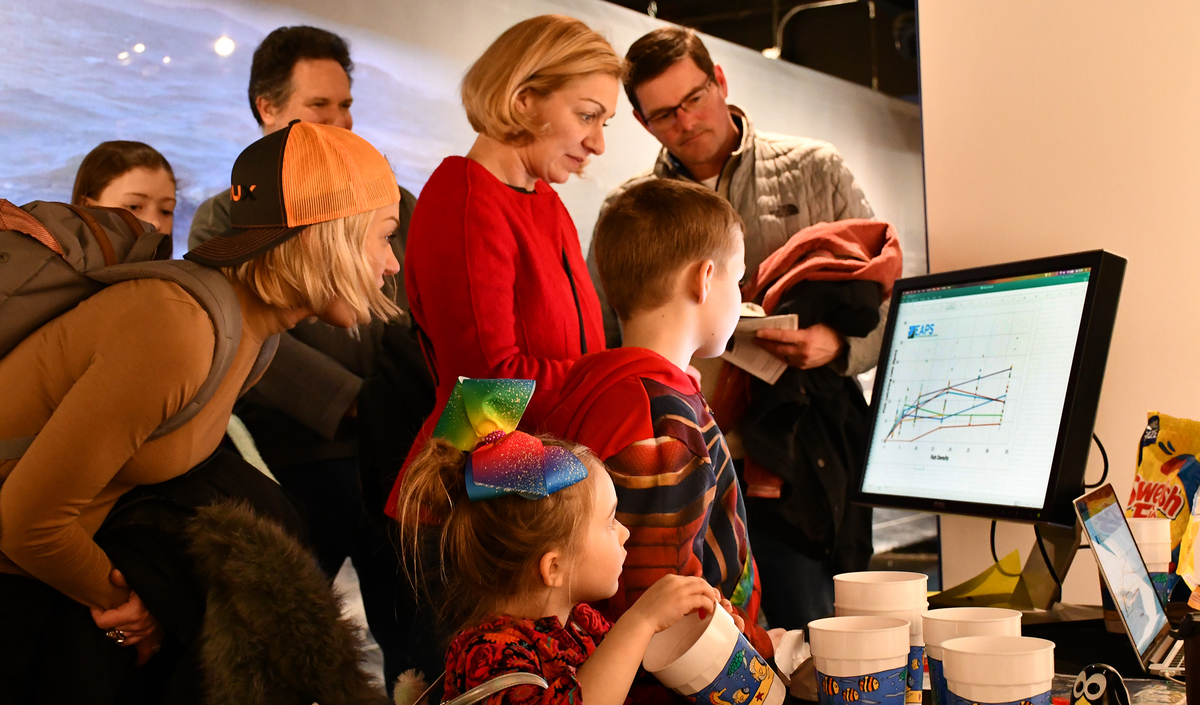

This is not a question asked often of Jonathan Lauderdale and Maike Sonnewald, postdocs in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) and Program in Atmospheres, Oceans and Climate (PAOC) members. But this past Saturday, February 23, 2019, Lauderdale and Sonnewald presented at the MIT Museum’s 2019 Nautical Day, an annual event that offers hundreds of guests from the greater Boston area hands-on lessons in ocean and climate research.

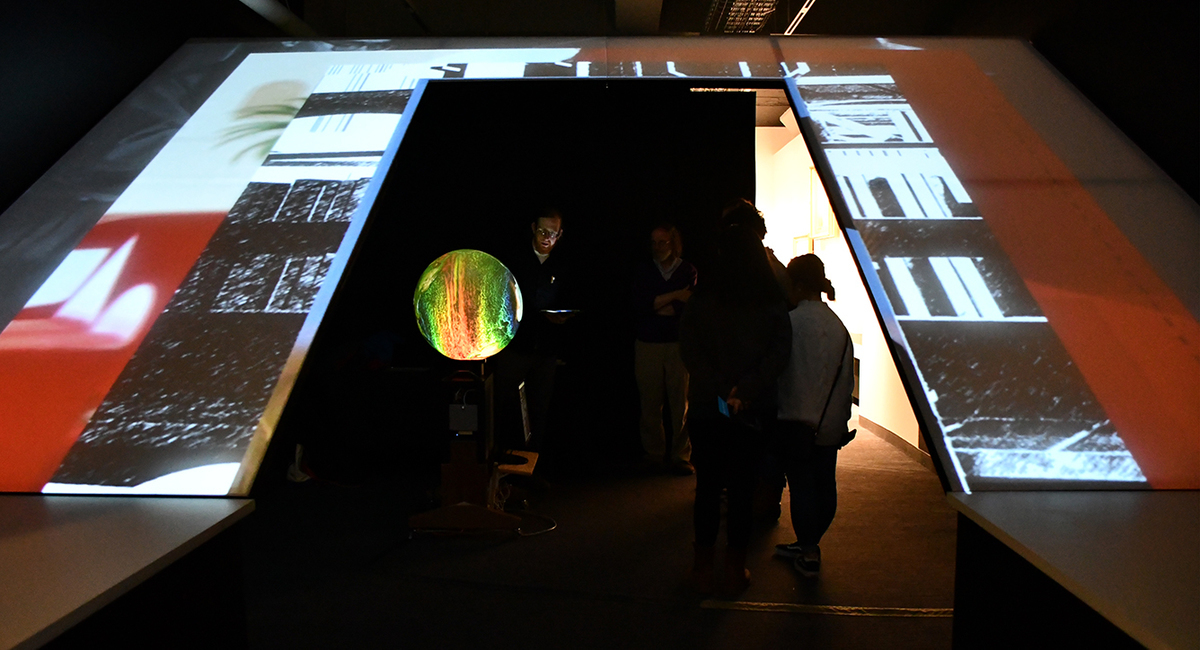

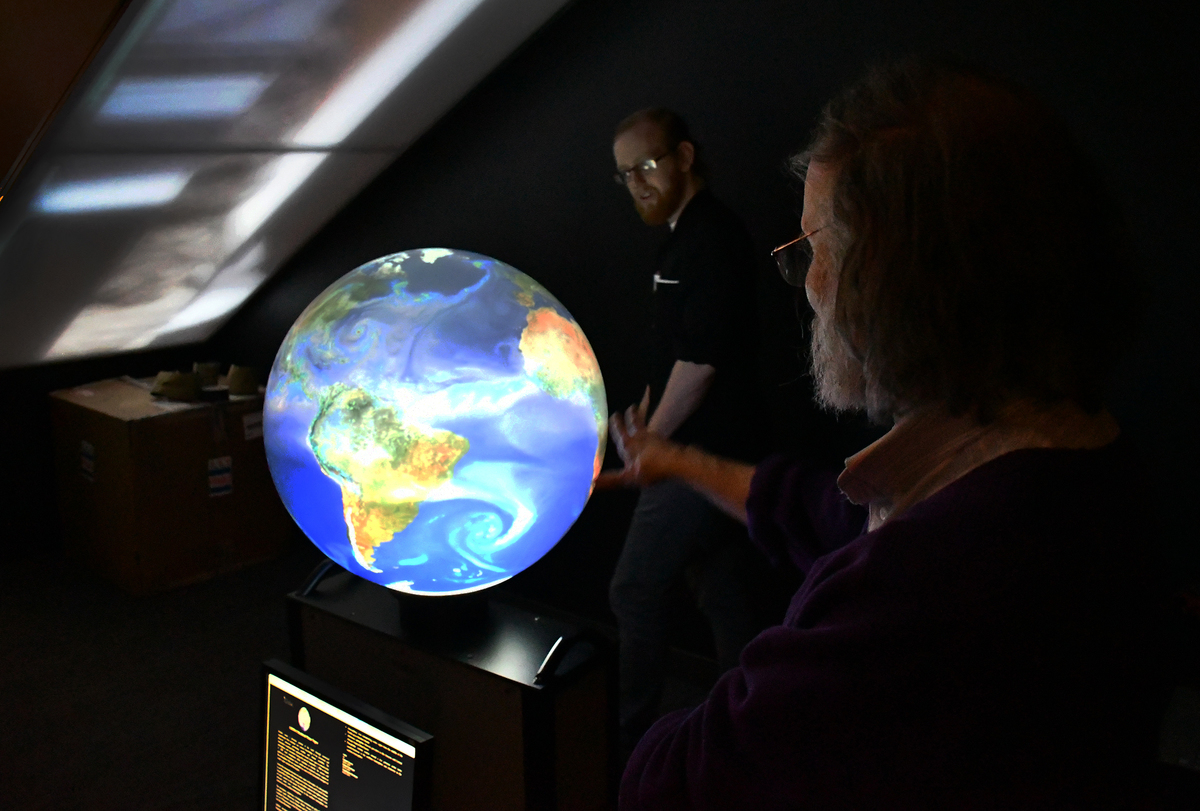

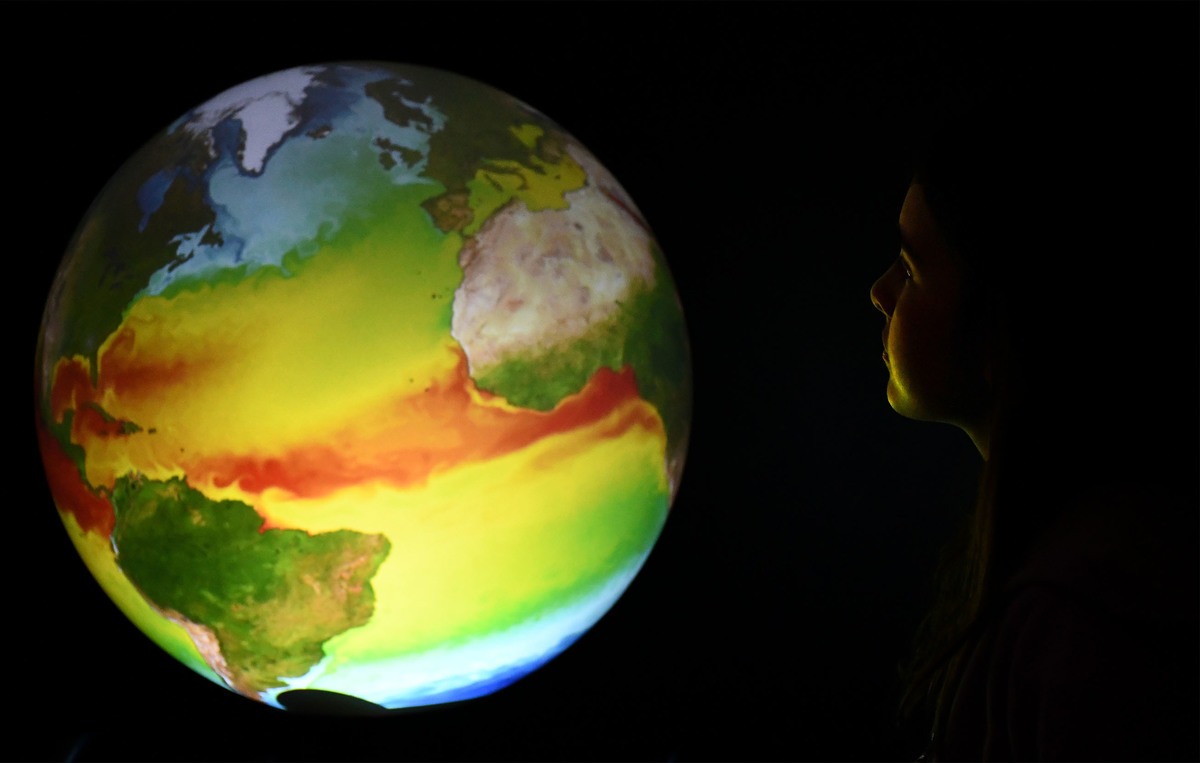

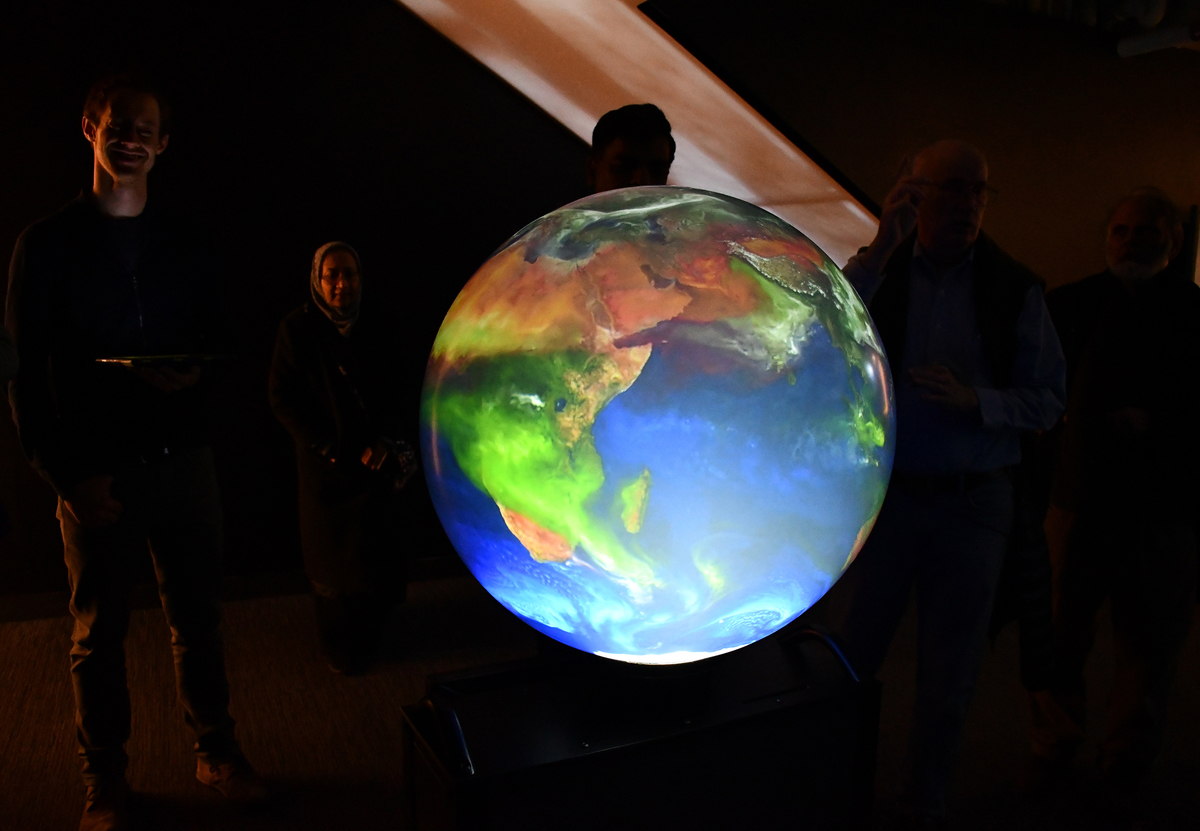

In one of two ocean-themed attractions hosted by PAOC members this year, Lauderdale and Sonnewald used a simple Swedish Fish game to model connections between food abundance and predator consumption, inspired by principles put forth by ecologist Crawford Stanley (Buzz) Holling. In the second attraction, just across the hall, attendees experienced the mesmorizing graphics of iGlobe, an illuminated 2-foot sphere with a rotating display of maps and data visualizations related to climate and environmental concerns, hosted by Bill McKenna, a researcher and technician in the Synoptic and Fluid Labs in EAPS, Samuel Levang, graduate student in the Flierl group, and Glenn Flierl, EAPS Professor of Oceanography.

This was the seventh consecutive year that PAOC members participated in Nautical Day, and both interactive lessons drew big crowds of all ages. Guests may have been lured in by the candy or spellbinding graphics but they left with a new appreciation of weather, oceans, or climate science. The following photos give a glimpse into what they experienced.

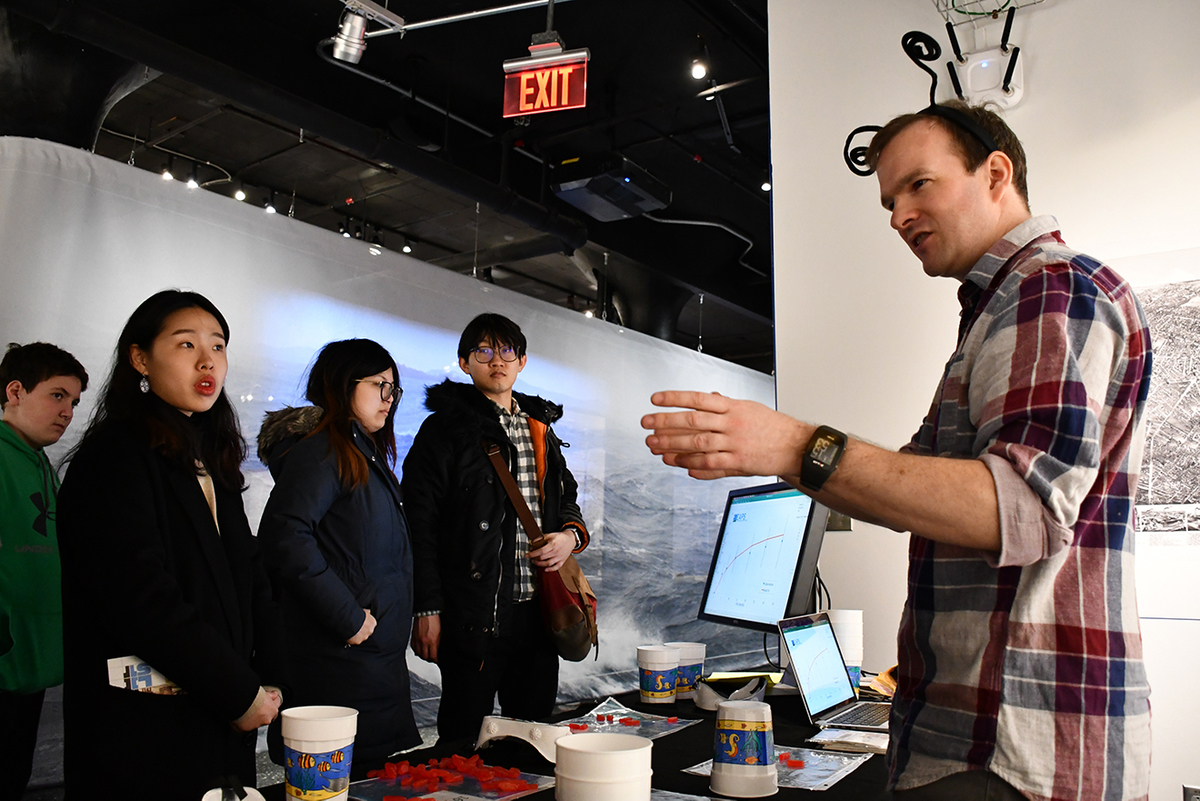

Once averaged, the data fit a curve predicted by Holling, as shown on the screen behind Lauderdale.

In this way, guests could see how predators with little prey (the placemats with 2 or 4 Swedish Fish) spent most of their time hunting for fish unsuccessfully, while those with an overwhelming amount of prey (placemats with 16 or 32 Swedish Fish) had plenty but were limited by how fast they could consumed the prey. This relationship, explained Lauderdale, is how ocean modelers turn marine ecological phenomena, like phytoplankton abundance, into mathematical relationships to model how life in the ocean will behave.

The iGlobe/MIT project is funded by the National Science Foundation.