PAOC Spotlights

MIT-WHOI Joint Program Marks 50th Year

Read this story on Oceanus Magazine.

In 1968, two esteemed scientific institutions launched an unorthodox academic experiment: Each would remain fiercely independent, but they would jointly coordinate a graduate program to educate and train ocean scientists and engineers.

Today, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology-Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Joint Program in Oceanography and Applied Ocean Science and Engineering is world-renowned, boasting more than 1,000 alumnae/i who became leaders in the field and made valuable contributions in research, teaching, government, industry, and the Navy.

To toast their golden anniversary, the two institutions celebrated with two days of festivities on Sept. 27-28 on their respective campuses in Cambridge and Woods Hole, Mass. They included a symposium in MIT’s Wong Auditorium with faculty, guests, and alumnae/i with a diverse range of careers and a reception at WHOI with reflections from Joint Program leadership on the program then and now.

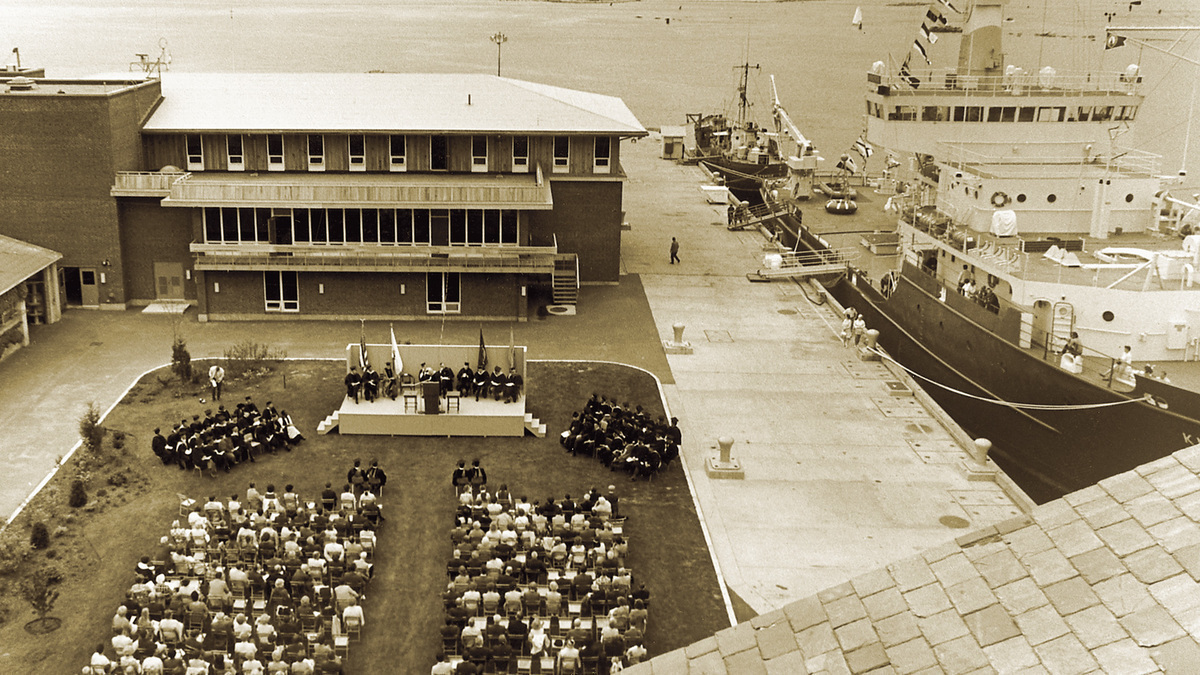

The 1968 memorandum of agreement between MIT and WHOI was signed aboard the research vessel Chain at a time of both scientific and political fervor for ocean sciences. Convincing evidence had just been published for the theory of plate tectonics and was revolutionizing understanding of the oceans and Earth. The Stratton Commission on U.S. ocean policy was formulating sweeping recommendations “to stimulate marine exploration, science, technology, and financial investment on a vastly augmented scale.”

MIT was among the foremost centers of higher education in science and engineering. WHOI scientists were pioneering ocean instruments and vehicles and launching them from research ships from their port. One could provide top-of-the-line coursework; the other offered unparalleled fieldwork.

“The connection was natural,” said Howard W. Johnson, president of MIT at the time. But the relationship was unprecedented.

“All decisions are done by consensus and joint committees,” said Margaret Tivey, Vice President and Dean for Academic Programs at WHOI, who—fittingly—shared the organization of the celebratory events with Edward Boyle, MIT Director of the MIT-WHOI Joint Program and Professor of Ocean Geochemistry, who earned his Ph.D. from the program in 1976.

“I was entranced by this great experiment, in which two splendid institutions”—so different in size and history and separated by geography—"decided to run a graduate program that hovers almost mystically between them, run by faculty of both places for students of both institutions,” said Joe Pedlosky at the MIT symposium. He became Doherty Oceanographer at WHOI in 1979 and taught in the Joint Program for 28 years.

“Our education of oceanographers and earth scientists contributes to the rational discussion of our natural world—how it functions, how it’s changing, why it is changing, and what to expect in the future,” Pedlosky said. “It produces capable scientists that become a technical, focused resource, and an intellectual one that strengthens citizenry’s ability to confront real problems productively.”

“Our shared commitment to improving the understanding of the marine world and to the important mission of training new generations of marine scientists have kept us working productively for over a half century,” said Maria Zuber, Vice President for Research at MIT.

“We in the Navy think of this [program] as just a jewel, a bright star in the constellation of possibilities in ocean sciences,” said Admiral John Richardson, Chief of Naval Operations for the U.S. Navy, who earned three master’s degrees from the Joint Program in 1989. “MIT, WHOI, and the Navy have a rich history … of teaming together to tackle some of the toughest challenges that face our nation.”

“So much of our nation’s prosperity and our well-being is tied up and connected to the ocean,” Richardson said. He cited the 90 percent of trade goods transported by ships, transoceanic communications cables, the rising search for energy, mineral, and food resources in the ocean, and the preponderance of big cities located on the coast.

MIT-WHOI Joint Program faculty and graduates have also made significant contributions to advancing the science of climate change and informing policymakers' understanding of climate change and its impacts, said John Holdren, President Barack Obama’s Science Advisor, who gave the symposium audience a concise political history of the climate change debate.

Several other Joint Program alumnae/i told stories about their experiences in the JP and their careers afterward:

• Heather Goldstone, Ph.D. ’03, a science journalist for WCAI and WGBH National Public Radio and host of a weekly science radio news show, Living Lab, who spoke about scientists’ responsibility to promote science literacy.

• Hedy Edmonds, Ph.D. ’97, who is Lead Director of the National Science Foundation’s Chemical Oceanography Program, talked about the central role that chemical oceanography plays in ocean processes—even if it does not have the charisma of waves or dolphins.

• Oscar Pizarro, Ph.D. ’05, Principal Research Fellow at the University of Sydney, related his story about bringing robotic undersea vehicles developed at WHOI to launch a program to monitor coral sites and other marine habitats around Australia.

The final alumni speaker, Matt Jackson, Ph.D. ’08, said that when he first came to WHOI as an undergraduate Summer Student Fellow, WHOI geochemist Stan Hart had just come back with a map of an undersea volcano at the eastern end of the Samoan Islands that was bigger than Mount Fuji in Japan. But he had no evidence that the volcano, called Vailulu’u, was active. In his third year in the Joint Program, however, Jackson was aboard a ship mapping Vailulu’u and found that in the intervening six years, a 1,000-foot cone had grown within the volcano’s crater.

“This was a volcano that I came to study and wasn’t sure was going to be active, and here’s the smoking gun!” he said.

That has been a hallmark of the Joint Program, said Chawalit Charoengpong, a current Joint Program student: Students have extraordinary access to exciting fieldwork and quickly become part of research teams doing cutting-edge research. Their relationship with faculty is less professor-to-student and more colleague-to-colleague, he said.

“Graduate students have helped my career and were involved in everything we did,” said Sallie (penny) Chisholm, MIT JP director from 1988 to 1995.

“Anyone who has worked with JP students or seen them in action knows how they contribute to the WHOI culture and research,” said James Yoder, WHOI Dean of Academic Programs from 2005 to 2016. “In fact, it’s hard to distinguish between JP education and research.”

Of the roughly 700 scientific papers published per year by WHOI scientists, more than 100 are co-authored by JP students, Yoder said. On about 60 papers per year, JP students are first authors.

Chisholm and Yoder joined a parade of former JP directors and deans who spoke at the 50th anniversary events at WHOI, along with WHOI’s John Farrington (1990-2005) and MIT’s Art Baggeroer (1983-1988). MIT’s Marcia McNutt (1995-1997) and Paola Rizzoli (1997-2009) sent videotaped remarks.

The audiences at the MIT and WHOI receptions applauded the announcement that Delle Maxwell and Pat Hanrahan made combined $2.5 million gifts in honor of their father and father-in-law, Arthur E. Maxwell. In 1965, Maxwell joined WHOI, serving as WHOI’s Director of Research and Provost and playing an instrumental role in the development of the Joint Program.

A $1 million gift goes to the Arthur E. Maxwell Graduate Student Fund at WHOI, established in 2003 by Jamie Austin, Ph.D. ’79, to honor his mentor. It provides annual support for first-year graduate students. A $1.5 million gift goes to the MIT Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences to endow the Maxwell-Hanrahan Fund for Education and Research, which will fund opportunities for students to carry out oceanographic research at sea.

Tivey cited the importance of gifts like these, starting with the foundational gifts by the J. Seward Johnson Fund and the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation Fund, which launched the Joint Program. “We could not run the program without these gifts,” she said.

To date, the program has awarded 1,053 degrees (764 doctoral, 58 engineer’s, and 231 master’s degrees). Since 1999, it has had roughly an equal split between men and women and between 2013 and 2017, 59 percent of the Ph.D.s were awarded to women.

“What would life on Earth be like without healthy oceans?” Zuber said. “For the sake of all Earth’s life forms, it’s imperative that we continue to improve our understanding of the oceans and the way we interact with them.”

“Never before has an oceanographic education been so important,” Jackson said. “Basic research is desperately needed on Earth’s remaining frontier. Oceans are ground zero for climate changes, rising sea levels, ocean acidification, new species, coral reef damage, deep-sea mining, and impacts on marine ecology. These are huge issues, some of the most pressing issues we face, and the MIT-WHOI Joint Program is perfectly positioned to train scientists to address these issues.”