PAOC Spotlights

Leading The Way

In honor of Women’s History Month, PAOC celebrates three female scientists who left indelible marks on MIT and the field of oceanography and climate science as a whole.

Paola Malanotte-Rizzoli, the first woman to get tenure in EAPS

Audentes fortuna iuvat, wrote Paola Malanotte-Rizzoli in an autobiographical article for the Annual Review of Marine Science. Fortune favors the bold—and Malanotte-Rizzoli would know. Throughout her extraordinarily multifaceted career, Malanotte-Rizzoli has spurred bold new research and garnered well-deserved accolades in the previously male-dominated field of physical oceanography.

Born in Vicenza, Italy, Malanotte-Rizzoli began her career in Venice as a physicist working on the Venetian Gates project before heading to the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego in the 1970s. After a brief tenure as a visiting scientist, she began her doctoral degree in 1974 at Scripps, where she was the only female student in the physical oceanography program. Four years later, when she successfully defended her thesis, Malanotte-Rizzoli became the first woman in Italy to obtain a PhD in physical oceanography.

Malanotte-Rizzoli continued to break down gender barriers when she arrived at MIT in 1981 after being hired as an assistant professor by Edward Lorenz, then Head of the Department of Meteorology and Physical Oceanography. In 1983, the Department merged with the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, and in 1987, Malanotte-Rizzoli became the first woman to get tenure in the newly formed Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences at MIT. "She is considered by her Department to be the leading woman oceanographer in the world,” reads an issue of Tech Talk from November 4, 1987, listing the newly tenured professors.

Today, Malanotte-Rizzoli is considered a leader and true Renaissance woman in the field of physical oceanography, having made significant contributions in theoretical fluid dynamics, numerical modeling, acoustic tomography, and more. For the next generation of students, Malanotte-Rizzoli has this advice: “Better to try and fail than refuse the challenge because of fear. This is the best advice I can give to any student or young scientist: Be bold, grasp your Fortuna, and build upon it.”

Read Malanotte-Rizzoli’s 2017 autobiographical article, titled “Venice and I: How a City Can Determine the Fate of a Career,” here.

Kathryn A. Burns, the first woman to graduate from the MIT/WHOI program

In 1970, Kathryn Burns ignored advice to spend her wedding money on a new refrigerator and instead bought a bright yellow eight-foot dinghy, named Chicken, which she used to move with her husband to Woods Hole, MA, to join the first MIT–WHOI Joint Program in Oceanography class to include female students.

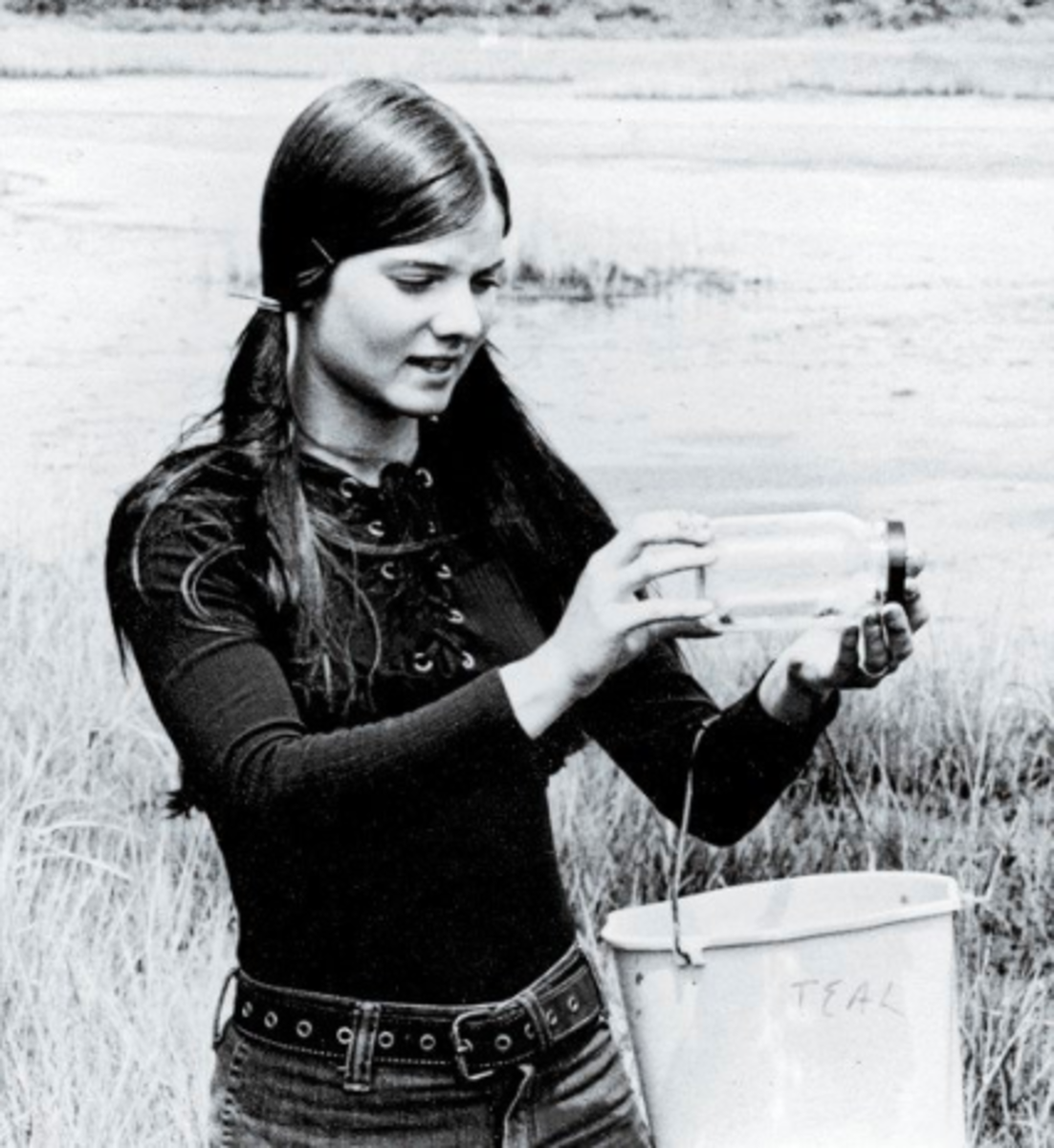

Burns’ work as a graduate student at WHOI shed light on the disastrous ecological consequences of the 1969 oil spill in Buzzards Bay, which released 700,000 liters of the toxic sludge into the previously pristine marshes. To document how the ecosystem recuperated, Burns studied how different animals metabolized and excreted contamination left behind after the spill. For example, marsh minnows, she discovered, could process toxins from oil up to 100 times faster than the fiddler crabs thanks to their ability to ramp up production of mixed-function oxidases, which break down oil.

Five years after she arrived, Burns published her doctoral thesis, “Distribution of Hydrocarbons in a Salt Marsh Ecosystem After an Oil Spill and Physical Changes in Marsh Animals from the Polluted Environment,” and became the first woman to graduate from the MIT/WHOI joint program. Today, Burns is an adjunct scientist at TropWATER at James Cook University in Australia, and her early work at Buzzards Bay remains a touchstone in ecological recovery after oil spills. Read more about Burns via a MIT Technology Review profile or Burns’ memoir, Science and Sails.

Eugenia Kalnay, the first woman to receive a PhD in meteorology from MIT

As the newly appointed Branch Head at the Goddard Space Flight Center, Eugenia Kalnay found a solution to being interrupted during meetings. At the advice of a colleague, she employed the Quaker tradition of “working by consensus,” which much to her surprise proved to be successful. The collaborative approach—“plus gentle nudging”—put an end to the interruptions by male scientists, Kalnay told interviewers for the Inter-American Network of Academies of Sciences.

Kalnay made similar headway for gender equality in science in 1971 when she became the first woman to receive a PhD in meteorology at MIT. Kalnay had come to MIT from Argentina in 1967 after violent protests erupted at the University of Buenos Aires, where she had been a teaching assistant, and her advisor, meteorologist Rolando Garcia, put her in touch with Jule Charney. When she arrived, Kalnay was the only female student in the Department of Meteorology. Later, she would become the first female professor in the department before leaving to join NASA Goddard in 1979.

Today, Kalnay is a Distinguished University Professor in the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Science at the University of Maryland and leading expert in numerical weather prediction. Her 2003 textbook "Atmospheric Modeling, Data Assimilation and Predictability" is still widely used in graduate courses. She has received two gold medals from NASA, and in 2009, was won the IMO Prize of the World Meteorological Organization, becoming only the second woman to win the prestigious award. Her current research focuses on coupling ocean-atmosphere models with human system models (on things like population and economic factors) to study climate change and sustainability efforts.

Kalnay’s advice to other women scientists: “The most important advice is to work on what you like to do, without worrying about money or recognition, which will come if you put passion in your work. Learn to speak clearly, briefly and forcefully, and don't allow others to interrupt you!” Read Kalnay’s full interview with IANAS here.