PAOC Spotlights

4 Questions with David Battisti on El Niño and Climate Variability

Atmospheric Scientist David Battisti discusses the double El Niño phenomenon and what it does and doesn’t tell us about climate change.

***

This year’s spring Houghton Lecturer is David Battisti, a professor of atmospheric sciences and the Tamaki Endowed Chair at the University of Washington. As the scientist-in-residence within MIT’s Program of Atmospheres, Oceans, and Climate (PAOC), Battisti has spent the semester giving a series of talks on natural variability in the climate system. Some of his main research interests include illuminating the processes that underlay past and present climates, understanding how interactions between the ocean, atmosphere, land, and sea ice lead to climate variability on different timescales, and improving El Niño models and their forecast skill—something that is becoming increasingly relevant in a warming world.

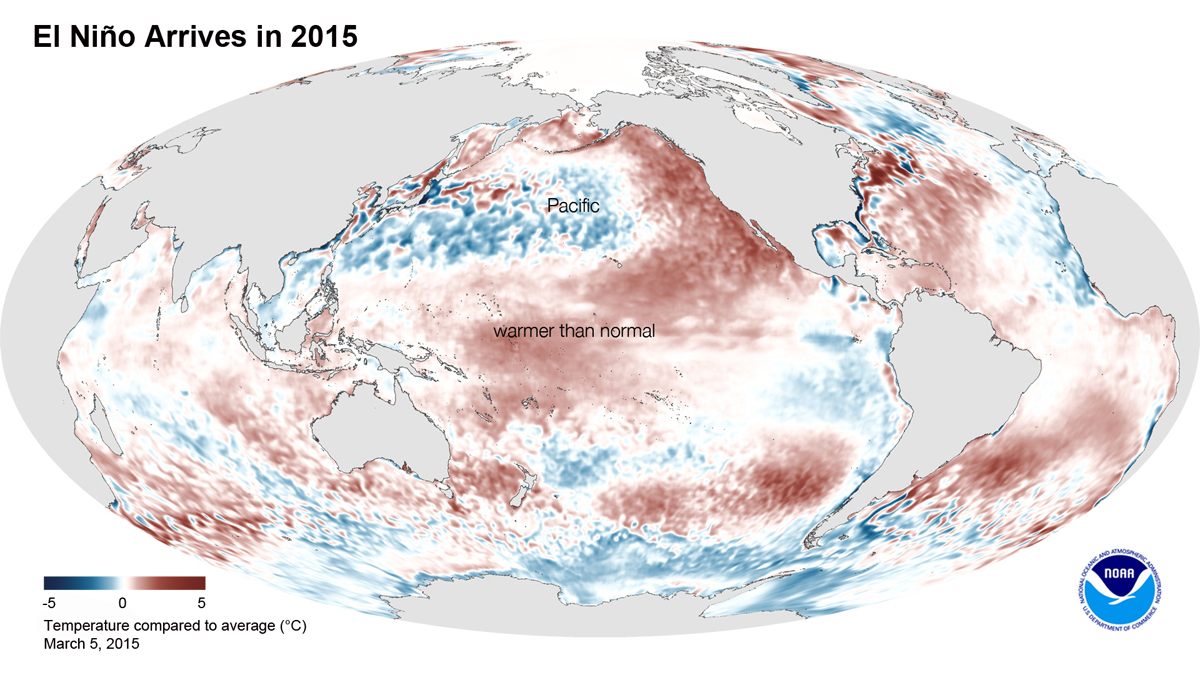

The Pacific Ocean is primed for a powerful double El Niño—a rare phenomenon in which there are two consecutive years of episodic warming of sea surface temperatures—according to some scientists. It’s been a few years since the Pacific Ocean experienced one strong warming event, let alone an event that spanned two consecutive years. A double El Niño could have large ripple effects in weather systems around the globe, from summer monsoons and hurricanes to winter storms in the Northern Hemisphere. Meanwhile, some scientists think it may signal the beginning of the end of the warming hiatus. Oceans at MIT asked Battisti about this phenomenon and what it does and doesn’t tell us about climate change.

How rare are double El Niños and what are the expected effects?

[Double El Niños] are not unheard of, but the last time it stayed warm for nearly two full years was back in the early 80s. In the tropics, climate anomalies associated with a typical El Niño event will persists as long as the event persists. For example, El Niño warm and cold events explain the lion’s share of the variance in monsoon onset date: conditions in late boreal summer causes a delay in the onset of the monsoon in Indonesia, which greatly reduces the annual production of the country’s staple food, rice. If El Niño conditions persist for two years spanning the onset time for the Indonesia monsoon, monsoon onset will very likely be delayed for two consecutive years.

In the mid-latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere, where we live, El Niño affects the climate by issuing persistent, large scale atmospheric waves from the tropical Pacific to the North Pacific and over most of North America. These waves are most efficient at reaching the mid-latitudes during our wintertime. If El Niño conditions span two consecutive northern hemisphere winters, we should expect the winter climate in these regions to be affected similarly over two consecutive winters.

During an El Niño event, there is a greater than normal chance for an unusually warm winter in the Pacific Northwest and in the north central US, and for a colder and wetter than normal winter in southern Florida. Alternately, El Niño has little impact on winter weather in New England. It also greatly affects precipitation in Southern California and the southwestern US — El Niño years are reliably wetter than normal, but just how much wetter than normal is very unpredictable.

Why haven’t we seen a strong El Niño in nearly two decades?

A large El Niño event is characterized by exceptionally warm conditions in the tropical Pacific, or by very warm conditions that persist for 18 months or so – about nine months longer than normal. It’s been over 20 years since we’ve seen a very large warm event, but it is not known how frequently very strong and exceptionally long events happen.

We categorize El Niño events (and their cold event siblings) by measuring sea surface temperature and zonal surface wind stress along the equator in the tropical Pacific. Good data to construct these indices extend back to the early 20th Century. Unfortunately, we can’t answer this question by examining the behavior of the high-end climate models because about only two high-end climate models in the world feature El Niño warm and cold events that are consistent with observations. However, the observational record shows three El Niño events with exceptionally large amplitude that were exceptionally long lived since 1950s, so a 20-year gap since the last large warm event is not surprising.

What does the hiatus refer to, and is it related to the El Niño phenomenon?

The whole hiatus idea is based on the expectation that as carbon dioxide increases, so to should the global average temperature. And indeed, the global averaged temperature has increased over the course of the 20th Century by approximately 0.85 degrees Celsius. And climate models support that the primary reason the 20th Century increase is rising concentrations of greenhouse gases associated with human activity. However, over the past dozen years or so, the global average temperature has not increased – hence the moniker ‘the hiatus’.

The decade long hiatus isn’t inconsistent from what we would expect from natural variability and human forced climate change. For example, a typical El Niño cycle features a very warm year, followed by a moderately cold year, and then nothing happens for a while. Somewhere between three and seven years later there’s another warm event followed by a cold event, but the duration between these events is quite random. Selecting any single period—for example, the last 10 years—we would expect decades in which the global average temperature fluctuates by 0.15 degrees Celsius or so due to the randomness in natural climate variability. The regional patterns of temperature change and the hiatus in global average temperature over the past decade aren’t distinguishable from a superposition of the cold phase of natural variability with the expected warming due to human activity.

Is this a sign that the warming hiatus is coming to an end?

El Niño does increase the global average temperature so we will see the average global temperature spike a bit this year compared to the last few years, which will bring us back up toward what the models say is the forced warming response. But El Niño events are not predictable more than a year or so in advance, so it is not possible to say what will happen over the next few years, or even the next decade.

On the other hand, if you view the change in global average temperature over the past thirty years as being a superposition of a steady increase due to human-induced forcing and decade-long periods of warm (the 1980’s and 1990’s) and cold (the 2002-2013) anomalies due to natural variability including El Niño, then decade-long periods of very large warming and very weak warming or even weak cooling should be expected. Exactly when these periods end is only obvious in retrospect.

***

For 25 years, Henry Houghton served as Head of the Department of Meteorology—today known as PAOC. During his tenure, the department established an unsurpassed standard of excellence in these fields. The Houghton Fund was established to continue that legacy through support of students and the Houghton Lecture Series. Since its 1995 inception, more than two dozen scientists from around the world representing a wide range of disciplines within the fields of Atmosphere, Ocean and Climate have visited and shared their expertise with the MIT community.