For the good of the colony

For the good of the colony

For some microbes, the motto for growth is not so much “every cell for itself,” but rather, “all for one and one for all.” MIT researchers have found that cells in a bacterial colony grow in a way that benefits the

community as a whole. That is, while an individual cell may divide in the presence of plentiful resources to benefit itself, when a cell is a member of a larger colony, it may choose instead to grow in a more cooperative fashion, increasing an entire colony’s chance of survival.

“Once cells make that decision to live as a communal set of organisms, what other things do they have to start doing to make living as good as possible?” asks Chris Kempes, who did much of the work as a graduate student in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences. “Once you enter into that intimate cooperation with neighboring cells to benefit the group, it starts to hint at becoming complex, multicellular life.”

Kempes and his colleagues explored the dynamics of communal growth in the bacterial species Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a common strain found in soil and water that can cause infection in humans — particularly in cystic fibrosis, in which thick bacterial biofilms spread through the lungs, making it difficult to breathe.

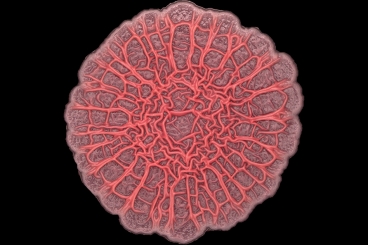

The team paired laboratory experiments with theoretical modeling to show that as a colony takes shape, it not only grows outward, but also upward, forming a complex pattern of ridges, or wrinkles. This wrinkling, the researchers hypothesized, acts to increase the surface area with which a colony can take in oxygen and grow.

Through simulations, the group could predict the pattern of wrinkles based on certain environmental and genetic factors, such as the amount of oxygen available. In particular, the team observed that as wrinkles form, at a certain point, the cells involved continue to grow in height, but not in width. Wrinkles grow upward once they’ve reached a certain width — a width, it turns out, that is optimal for the success of the colony as a whole.

“This starts to hint at some really interesting cooperative dynamics going on,” says Kempes, who is now a postdoc at NASA’s Ames Research Center and a principal investigator at the SETI Institute. “This really paints a picture of how this community geometry responds to a variety of factors and finds what’s best for the growth of the entire community.”

Kempes and co-authors Lars Dietrich, Chinweike Okegbe, and Zwoisaint Mears-Clarke of Columbia University and Mick Follows of MIT have published their results this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

...Continue reading this story at MIT News